Showdown! Colt v. Winchester; High noon, with the “Guns That Won The West.”

Showdown! Colt v. Winchester; High noon, with the “Guns That Won The West.”

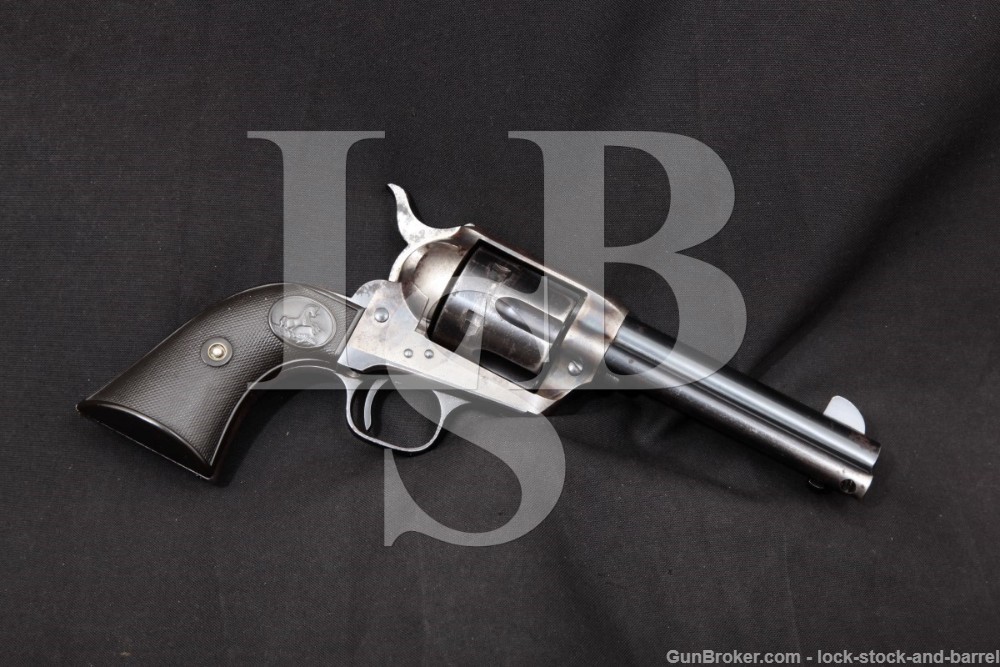

Ask any western firearms aficionado which gun won the West, and you’ll have pretty universal agreement that it was the 1873. Ah; but which 1873? In 1873, if a lawman or outlaw meant business, it meant packing a Colt Peacemaker 1873 SAA. Or, maybe an 1873 Winchester rifle. Or, likely, both.

Each served admirably in the role for which it was designed. But how Colt became synonymous with the revolver, and how the Winchester 1873 became the iconic rifle is an interesting tale. And not necessarily a peaceful one.

In 1855, having built firearms via subcontractors for nearly two decades, Colt’s Patent Firearms Manufacturing Company began producing their own firearms in a proprietary factory in Connecticut. Samuel Colt had been a mover and shaker in weapons design for some time previous to that; however his 1836 Paterson design had marked a revolution in firearms development, and his powerful 1847 Walker model gained fame as a handy and devastating weapon.

By 1861, the outset of the Civil War, Colt was one of the wealthiest men in America, although he didn’t live to see the end of the conflict. When he died in 1862 at age 47, the company that bore his designs and innovations carried on, providing thousands of firearms to the federal government, and gaining unprecedented wealth and influence in the process. When the bloody but lucrative days of the Civil War came to an end, Colt Manufacturing attempted to diversify their product line. Gathering up patents and talented designers, they refined their revolver so that in 1873, their Single Action Army model was formally adopted by the U.S. military. Out west it headed, in the holsters of soldiers, lawmen, outlaws, and civilians alike, and so was in a position to become, “The Gun That Won The West.”

Something must have been in the water in Connecticut in the 1800s; across the state, Oliver Winchester was also having a grand career. Winchester was initially a successful clothing manufacturer who was also the majority stockholder in the innovative Volcanic Repeating Arms Company. When Volcanic’s underpowered and reliability-plagued model floundered, Volcanic’s talented designer, Benjamin Henry, fueled by Winchester’s money, expanded on the earlier design tube-fed magazine and lever repeating mechanism, and finished the more powerful and reliable Henry repeating rifle in 1860, just on the eve of the Civil War.

Though never as widely adopted or the beneficiary of lucrative government contracts as was Colt, the Henry rifle changed the face of battle with its rapid fire ability, and in little more than a decade, the design had evolved to become the 1873 Winchester; the “Gun That Won The West.”

And now, the story becomes truly interesting.

With the Civil War a painful memory, Colt’s salad days were a memory, as well. In 1872, Winchester hired inventor William Wetmore to design a single action revolver. This was a bold move, as it threatened Colt’s virtual monopoly on the pistol world, and the insular firearms community noticed. Wetmore’s work produced a practical design, and a workable Winchester pistol was created, robust, and intended to be produced at a lower price than Colt’s offering.

In 1873, Colt introduced the Single Action Army, and, already screwed into the military acquisition system, immediately drew fresh U.S. contracts. Winchester redoubled their efforts to win some of Colt’s market share.

In 1880, Oliver Winchester passed away. Flush with cash from their new U.S. contracts, in 1882, Colt’s Manufacturing, ever eager to gain even more of the firearms market in those turbulent times, contacted Andrew Burgess to design a lever-action rifle. By 1883, the new Colt-Burgess lever action rifle had begun rolling off Colt’s assembly lines. To Winchester, this was an affront as well as an economic slap in the face, and it meant a full-fledged trade war.

Winchester 1873 rifles had been selling well, and they retaliated by acquiring Colt’s disgruntled chief engineer, William Mason. With that done, they next announced plans to build their own line of rifles and revolvers. Then, for good measure, they began dumping their English built shotguns onto the market at loss-leader prices, driving down the sales of Colt’s side by side shotgun.

A ruinous trade war loomed, and both companies seemed likely to cut each other’s throats, while Remington and Smith & Wesson were quietly lurking in the shadows, ready to pounce.

At this point, it apparently became obvious to both Colt and Winchester’s respective boards of directors, that the only likely winners to this industrial warfare were outside parties.

While no internal memos exist, cooler heads must have prevailed. In 1884, four years after Winchester’s death, top officials of the Winchester and Colt companies met to discuss the ongoing battle over market share. With the ruthless barons each peacefully in their graves, the companies forged an agreement that would see Colt stay on their side of the street, building pistols, while ceding production of lever action rifles to Winchester.

Winchester’s Wetmore single action revolver disappeared back into the vaults, never to see mass production, and the Colt-Burgess rifle was pulled from the market.

Of course, Colt must have had an ace up their sleeves, and written a pretty shrewdly narrow agreement, limited strictly to lever actions, because in 1884, Colt introduced their Lightning pump action rifle. But that’s a story for another time…